In September 2018, the group that would become the Resilient Mystic Collaborative (RMC) first gathered around a too-small conference table at Medford City Hall. I had been working with the City of Medford on their climate change vulnerability assessment as an intern and was looking forward to meeting and learning from other like-minded professionals at this meeting—a good networking opportunity for a second-year grad student. But I didn’t know it would frame my thesis work and career path.

Julie Wormser, Deputy Director of the Mystic River Watershed Association, convened this group of municipal staff and expert stakeholders to explore opportunities for regional climate change adaptation planning at the watershed scale. Throughout the morning, these professionals discussed their priorities for climate change adaptation in their own communities and for the region, and the more I listened, the more excited I became. This approach made so much sense to me; climate change impacts extend beyond our political boundaries, but some of them, like flooding, stay within the natural boundary of the watershed.

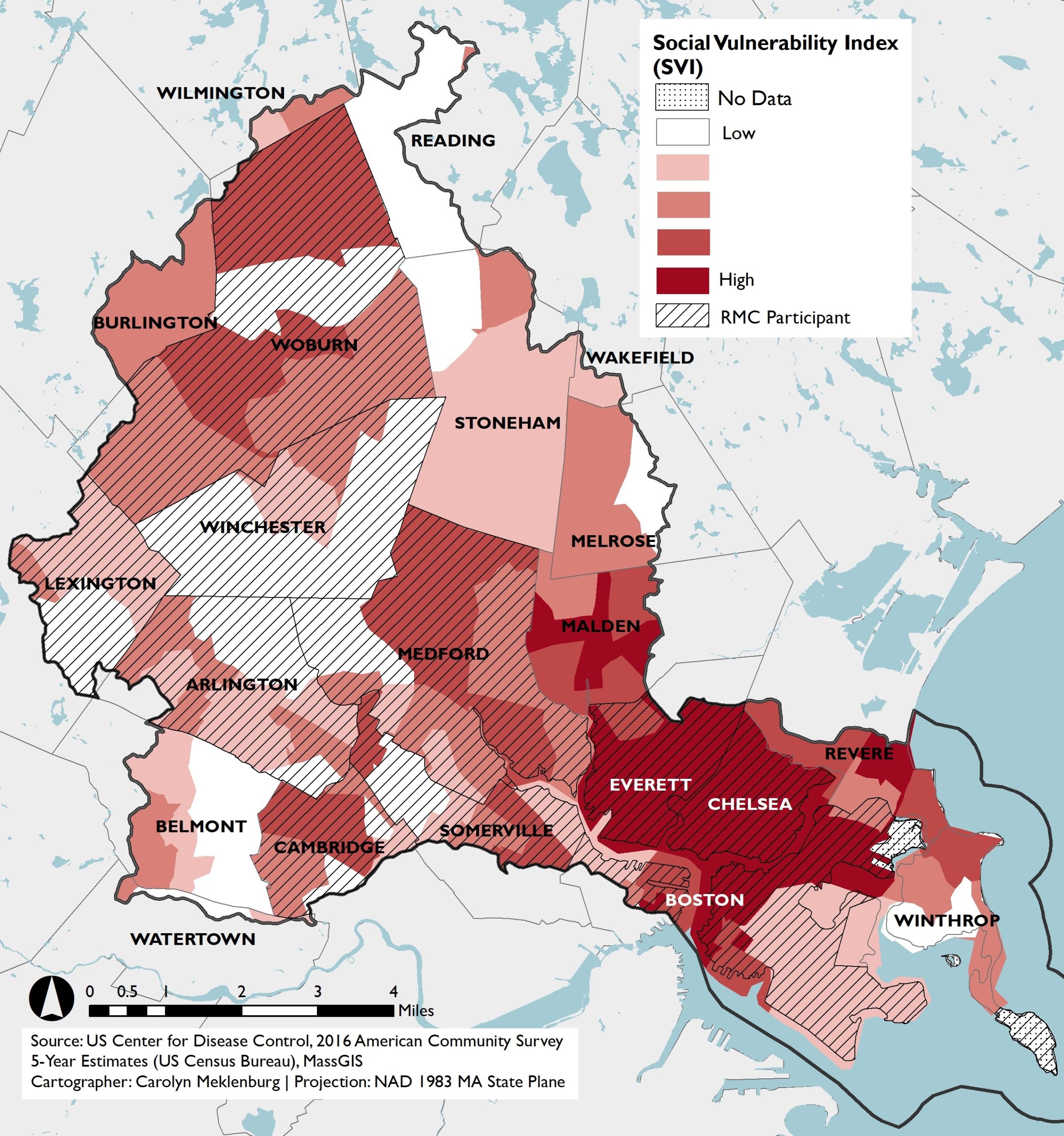

The Mystic in particular faces a variety of unique environmental and societal challenges. It is highly developed with more than half of its landmass covered in impervious surfaces, and home to many socially vulnerable populations facing systemic injustices.

Topics that sparked my interest the most at UEP were at the center of these rich conversations, from green infrastructure to environmental justice to action-oriented planning.

I continued to attend these meetings as I worked on turning my general interest in climate change adaptation into a focused thesis research question. I explored different approaches to climate change adaptation, and soon realized that the Resilient Mystic Collaborative was beginning something special. While there are studies of collaboratives for watershed management (Sullivan, White, & Hanemann, 2019; Compagnucci & Spigarelli, 2018; Serra-Llobet, Conrad, & Schaefer, 2016; Koebele, 2015), of collaboratives for regional climate change adaptation planning (Shi, 2019; Betsill & Bulkeley, 2006; Amundsen et al., 2010; Green, Leonard, & Malkin, 2018), and on integrating climate change adaptation into watershed management (Pahl-wostl, 2007; Binder, 2006), it is rare for a collaborative to combine watershed planning and climate change adaptation planning in the way that Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) is doing.

The RMC became my central case study as I explored the following research question: To what extent does collaboration at the watershed-level allow for the creation of regional climate change adaptation strategies that overcome barriers to the multi-jurisdictional stormwater problems intensified by climate change?

While the RMC’s approach is exceptional, I found some other groups that worked towards similar goals with varying approaches. The Cape Cod Commission is a regional planning agency that has regulatory authority over Barnstable County, which happens to encapsulate a single watershed. Its focus extends beyond climate change adaptation and environmental planning, but it was cited as a model for the RMC since it engages in watershed-based planning (J. Wormser, personal communication, February 7, 2019). The Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact was also cited as a model for the RMC since it is a well-established climate change group that focuses on the environmental impacts of land use planning and urban development (J. Wormser, personal communication, February 7, 2019). However, it is not specifically focused at the watershed scale. The Resilient Taunton Watershed Network (RTWN) is a collaborative group that addresses climate change adaptation at the watershed scale, but its core decisionmakers are regional planning agencies and non-profit organizations instead of municipal employees (B. Napolitano, personal communication, April 4, 2019).

In addition to researching some comparable groups, I also explored the process of collaboration itself: how does successful collaboration happen, and how can it be applied to climate change adaptation planning? There are several academic frameworks that have been used to analyze collaboration for environmental and watershed management. Since the RMC was just getting started—and wouldn’t be accomplishing its long-term goals within a semester and a half—I chose to assess its progress through the first three common stages of collaborative development: antecedent, problem-setting and direction-setting (Selin & Chavez 1995). From this analysis, I drew several key conclusions about the collaborative process in the context of watershed-based climate change adaptation planning

1) Collaboratives can fill a regulatory gap. Some studies argue that the threat of regulations is an antecedent for watershed collaboratives (Bentrup 2001), but the lack of regulations was a precursor for the RMC. Regulatory power within Massachusetts is granted to municipalities, not counties nor regional planning agencies. This poses a challenge for addressing multi-jurisdictional problems like climate change at scales larger than the municipality but smaller than the state. While Cape Cod addressed this problem by petitioning for and winning “home-rule authority” for Barnstable County to create the Cape Cod Commission (Lipman & Geist, 2011), this is not the norm. Many stakeholders mentioned in their early conversations with MyRWA that they believe zoning codes and building codes need to be updated to account for the additional flooding that climate change is bringing to this area, and that it should be done at a regional scale to avoid the development “race to the bottom” (J. Wormser, personal communication, February 7, 2019). Of course, arguing for or against climate change adaptation regulations requires further study: literature on environmental collaboratives cites frustration with top-down environmental policies as a reason that the collaborative approach gained popularity in the 1990s (Kenney et al., 2000). But the fact remains that stakeholders in the Mystic River Watershed identified needs that regulations do not currently address and work collaboratively to address them.

2) Gather data before bringing your group together. The need for consistent data across a given region served as an impetus for both the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact (Shi, 2017) and the RMC (J. Wormser, personal communication, February 7, 2019). However, developing accurate data at a helpful scale can also be seen as a challenge for collaboratives, particularly when addressing climate change and stormwater. Discussions during RMC meetings revealed other data-related challenges included frequent updates to climate change projections and possible security risks when it comes to sharing information about municipal water infrastructure. With such daunting challenges surrounding a critical need, it helps spark collaborative work if there is some data available to you to prompt your actions and goal setting. For example, in the RMC, Cambridge already had some in-depth stormwater data, but wanted to add to it from the watershed perspective. This allowed them to shape a project very shortly after coming together, giving the group some early momentum (J. Wormser, personal communication, February 7, 2019).

3) Set realistic and concrete goals to keep members motivated, and when these goals are met—even the small ones—celebrate them! Developing solutions to identified problems and implementing them are important to RMC members: the first sentence in the RMC’s governance document is “We are action-oriented”. One RMC respondent to a survey I conducted emphasized that one of their goals for the RMC is to “ACTUALLY implement” programs, projects and initiatives that they plan. Such action-oriented goals could be as small as setting meetings with outside agencies to advance projects, or as significant as getting a grant. Regardless of the size of the accomplishment, RMC facilitators ensure that each one is marked by an encouraging and congratulatory email (plus some sweet treats at the next in-person meeting).

4) Collaboration provides access to resources and expands the professional capacity of its members, but the member needs to have enough capacity to be able to participate in the first place. Academic literature on collaboration commonly refers to this rather obvious benefit of working together as “the collaborative advantage” (Vangen & Huxham, 2003). But I argue that it is equally important to recognize that this advantage further reveals a “capacity paradox.” The collaborative approach requires a significant commitment of time and resources, particularly at a larger scale. The RMC is only possible thanks to grant funding that allowed MyRWA to hire Julie Wormser as a full-time staff person as well as contracting with a professional facilitator (J. Wormser, personal communication, February 7, 2019). While they are in process of applying for more funding, relying on grants is not a sustainable approach for collaborating. Furthermore, municipalities represented in the early formation of the RMC had designated staff members who actively engaged in climate change-related work as a part of their role.

Although the collaborative offers the opportunity to access shared regional data and regional grant funding that may otherwise not be available to any one municipality, there were many communities not represented at these early meetings since they didn’t have a staff person available to send. Municipal employees are working their RMC participation into their standard workload without extra funding for now, but one member noted that if their participation is expected to increase as RMC projects expand, they may also require additional staffing or financial resources. The RTWN’s monthly meetings and consistent communication between members (B. Napolitano, personal communication, April 4, 2019), and the extensive staffing and budget of the Cape Cod Commission emphasize the commitment required for collaboration.

5) Trust is the foundation of collaborative work. Both the RMC and RTWN cite existing relationships between collaborative members as a significant factor in their early progress (B. Napolitano, personal communication, April 4, 2019; J. Wormser, personal communication, February 7, 2019). They had already worked with one another in various contexts, establishing a baseline of trust that everyone in the group was reliable and shared similar goals and values. It is critical that the act of collaboration continues to build on this pre-established trust. RMC facilitators purposefully integrate “ice-breaker” activities into every meeting to give collaborative members the opportunity to connect with colleagues both familiar and new. Trust between collaborative members and facilitators is also key. Ms. Wormser explains: “When people don’t trust meeting facilitators, they tend to question the agenda. People are allowing us to facilitate” (personal communication, February 7, 2019). By adjusting the meeting time and location to accommodate member needs, as well as ensuring that meeting time is used productively, RMC facilitators are reassuring collaborative members that they value their time, further fostering trust in their leadership.

I also identified some questions about the efficacy of watershed-based collaboration for climate change adaptation planning that would benefit from further study.

- How does conflict function in a collaborative setting, and how does the RMC experience (or not experience) conflict as they work towards their goals? What insights does this offer into collaborative work of this nature and scale?

- As the RMC grows, how do power dynamics between members impact the group’s process and outcome? This could include a difference between foundational members and more recent members, and/or a difference between representatives from more-resourced municipalities and less-resourced municipalities.

- Since there are no elected officials in the RMC, how do politics and the collaborative process interact, particularly as the group produces more concrete outcomes?

Since completing my thesis, I have had the opportunity to continue to witness the continued progress of the RMC. My familiarity with climate change adaptation initiatives in the region led me to my current position with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in which I actively work with municipal staff in the Greater Boston area to manage grant funding for local and regional climate change adaptation projects. I still participate in the RMC to further connect with communities that have grants I help administer. I’ve seen the group grow from representatives of fourteen communities to representatives of nineteen communities, representing municipalities that make up more than 90% of the watershed. It continues to receive grant funding from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts as well as from private foundations, most notably the Barr Foundation. Excitingly, their particular approach to climate change adaptation has extended to the neighboring Charles River Watershed: the Charles River Climate Compact began meeting earlier this year. I am grateful that I can continue to help communities build climate resilience beyond my thesis work, and to participate in the innovative approaches developing across our region.

References

- Amundsen, H., Berglund, F., & Westskog, H. (2010). Overcoming Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation—A Question of Multilevel Governance? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 28(2), 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0941

- Bentrup, G. (2001). Evaluation of a Collaborative Model: A Case Study Analysis of Watershed Planning in theIntermountain West. Environmental Management, 27(5), 739–748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002670010184

- Betsill, M. M., & Bulkeley, H. (2006). Cities and the multilevel governance of global climate change. Global Governance, 12(2), 141-. Retrieved from General OneFile.

- Binder, L. C. W. (2006). Climate Change and Watershed Planning in Washington State. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 42(4), 915–926. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2006.tb04504.x

- Compagnucci, L., & Spigarelli, F. (2018). Fostering Cross-Sector Collaboration to Promote Innovation in the Water Sector. Sustainability, 10(11), 4154. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114154

- Green, M., Leonard, R., & Malkin, S. (2018). Organisational responses to climate change: do collaborative forums make a difference? Geographical Research, 56(3), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12286

- Kenney, D. S., McAllister, S. T., Caile, W. H., & Peckham, J. S. (2000). The New Watershed Source Book: A Directory and Review of Watershed Initiatives in the Western United States. Retrieved from University of Colorado Boulder, Natural Resources Law Center website: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1031&context=books_reports_studies

- Koebele, E. A. (2015). Assessing Outputs, Outcomes, and Barriers in Collaborative Water Governance: A Case Study. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education, 155(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-704X.2015.03196.x

- Pahl-wostl, C. (2007). Transitions towards adaptive management of water facing climate and global change. Water Resources Management; Dordrecht, 21(1), 49–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11269-006-9040-4

- Selin, S., & Chavez, D. (1995). Developing a collaborative model for environmental planning and management. Environmental Management, 19(2), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02471990

- Serra-Llobet, A., Conrad, E., & Schaefer, K. (2016). Governing for Integrated Water and Flood Risk Management: Comparing Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches in Spain and California. Water, 8(10), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/w8100445

- Shi, L. (2017). A new climate for regionalism : metropolitan experiments in climate change adaptation (Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology). Retrieved from http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/111370

- Shi, L. (2019). Promise and paradox of metropolitan regional climate adaptation. Environmental Science & Policy, 92, 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.11.002

- Sullivan, A., White, D. D., & Hanemann, M. (2019). Designing collaborative governance: Insights from the drought contingency planning process for the lower Colorado River basin. Environmental Science & Policy, 91, 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.10.011

- Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2003). Enacting Leadership for Collaborative Advantage: Dilemmas of Ideology and Pragmatism in the Activities of Partnership Managers. British Journal of Management, 14(s1), S61–S76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2003.00393.x

Cover image by Daderot

Thank you for sharing your experience Carolyn. Great work! We at Tufts Institute of the Environment (TIE) are glad to see your continued accomplishments!

Comments are closed.